Affirmative action for college admissions is in crisis. To restore legitimacy we must democratise its definition of disadvantage

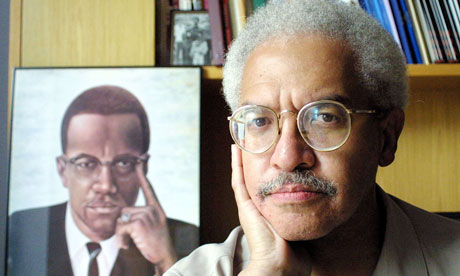

Manning Marable in his office at Columbia University beside a picture of Malcolm X in 2001. Photograph: Mario Tama/Getty Images

Manning Marable in his office at Columbia University beside a picture of Malcolm X in 2001. Photograph: Mario Tama/Getty ImagesIn his much-praised new biography, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, thelate Columbia University professor Manning Marable puts Malcolm in fresh perspective. He notes that Malcolm's picture of himself as the badass known as Detroit Red was often fictive, and he gives us the most detailed account to date of the assassination of Malcolm by five members of the Newark mosque of the Nation of Islam.

When it comes to Malcolm's politics, Marable is equally revealing. "Malcolm, had he survived to the 1990s, would not have been an enthusiastic defender of affirmative action as a centrepiece for civil rights reforms," Marable writes. "What Malcolm sought was a fundamental restructuring of wealth and power in the United States."

Marable's thoughts on Malcolm and affirmative action are particularly relevant to the current crisis American students are facing in higher education. These days, the future of affirmative action in higher education is in jeopardy. A series of states – among them, Michigan, California, Florida, Nebraska and Arizona – have banned the consideration of race, ethnicity or gender by any unit of state government, including public colleges and universities.

As a result, the state-run institutions of higher education with the greatest capacity for accepting minorities are increasingly less able to do so. Nor can these institutions turn to the public for support on affirmative action. By a 55% to 36% margin, voters believe affirmative action should be abolished altogether; and by a 61% to 33% margin, they oppose affirmative action for blacks in hiring, promotion and college entry,according to a 2009 Quinnipiac University poll.

This negative view of affirmative action in higher education can, in part, be explained by the rightward shift of the country since 1980, and the pressures the current recession has put on state budgets. But even more significant is the way in which affirmative action in higher educationhas all too often gone far beyond the "plus" factor in college admissions, which the supreme court said it should be, and simultaneously failed to reach the black population (those whose families were the victims of slavery and the Jim Crow south) for whom affirmative action was originally intended.

In No Longer Separate, Not Yet Equal, the most important study to date of race and class in college admission, authors Thomas Espenshade and Alexandra Walton Radford point out that preferences are large and significant, rather than a mere plus, for many minority students. On the SATs, in which 1600 is a perfect score on the combined math and verbal tests, selective private colleges and universities, for example, give black applicants an admission bonus of 310 points, and Hispanic students an extra 130 points; conversely, Asian applicants are penalised 140 points in the admissions game.

In addition, many of the black students receiving the 310-point admissions bonus are not from families that were ever the victims of slavery or Jim Crow laws. As William Chace, a strong defender of affirmative action and the former president of Wesleyan University and Emory University, recently noted, affirmative action now turns out to be helping considerable numbers of students "who have suffered the wounds of old-fashioned American racism little or not at all."

This issue of who should benefit from affirmative action came up in 2004 at a controversial meeting of Harvard's black alumni, in which it was pointed out that only about a third of Harvard's black students were from families in which all four grandparents were born in America and descendants of slaves. Other studies have shown that Harvard is not unique in the preferences it gives to black immigrants or the children of black immigrants. More than a quarter of the black students enrolled at America's selective colleges and universities are immigrants or the children of immigrants, and at schools such as Columbia, Princeton and Yale, two fifths of admitted black students are of immigrant origin.

But even among minority students who come from families that were once the victims of America's historic racism, the awarding of affirmative action benefits has been problematic. In higher education, the most vulnerable minority students – typically, those from poor, inner-city schools – have frequently been the ones affirmative action has ignored. These students have been too far behind educationally for affirmative action to help them. Instead, time and again, the minority students benefiting from affirmative action have come from middle-class families and attended good public and private schools.

As a consequence, among the sons and daughters of poor and working-class white families, affirmative action preferences as they now exist have stirred enormous resentment. These students have seen affirmative action benefits go not only to students whose families were never the victims of America's historic racism, but to students who are often wealthier and better-educated than them. The message these white students have taken is that, all too often, their problems don't count in the eyes of affirmative action's liberal advocates.

Such feelings have a factual basis. As Espenshade and Radford go on to note in No Longer Separate, Not Yet Equal, "The admission preference accorded to low-income students appears to be reserved largely for nonwhite students." The nation's best private colleges believe they have enough general access to whites, and so when it comes to investing in disadvantaged students, the colleges are motivated by the fact that nonwhites give them what whites cannot: a boost in their "multicultural" statistics and, by extension, better ratings in an influential publication like US News & World Report.

The result is an affirmative action crisis that, if nothing is done about it, will only get worse. Doing away with affirmative action entirely and leaving our colleges and universities to become white and Asian American enclaves is unthinkable, but so, too, is continuing an affirmative action system increasingly weakened by the broad political opposition it generates, and by the argument that it often benefits students with no basis for claiming special preferences.

The good news is that between these two poles lies a compelling alternative: to democratise affirmative action by making affirmative action preferences available to all students who have started out in life with disadvantages – whether caused by race, poverty, ethnicity, family or any other cause (for which they cannot be held accountable). The advantage of such a broad definition of affirmative action is that it avoids saying, as is now too often the case, that the disadvantages suffered by some college applicants are worthy of our sympathy, while those suffered by others are just tough luck. But there would be political benefits as well that come from putting affirmative action in a more inclusive framework.

Today, just 3% of the students enrolled in our most academically selective colleges come from the bottom quarter of the socioeconomic scale, and therein lies much of the resentment that many poor, white families feel toward affirmative action. A broadly conceived vision of affirmative action has the capacity to reduce such resentment. Instead of starting out with built-in opposition to affirmative action from those poor and working-class white parents who see their sons and daughters precluded from affirmative action preferences, an expansive approach creates another constituency with a stake in affirmative action's future.

This approach to affirmative action comes with the added benefit that it was, in essence, endorsed by President Obama while still an Illinois senator. When asked by ABC News's George Stephanopoulos, if his daughters should receive affirmative action preferences, Obama, a strong believer in affirmative action, replied, "I think my daughters should probably be treated by any admissions officer as folks who are pretty advantaged." Then he went on to add:

"I think we should take into account white kids who have been disadvantaged and have grown up in poverty and shown themselves to have what it takes to succeed."

No comments:

Post a Comment